By | Arvind Jadhav

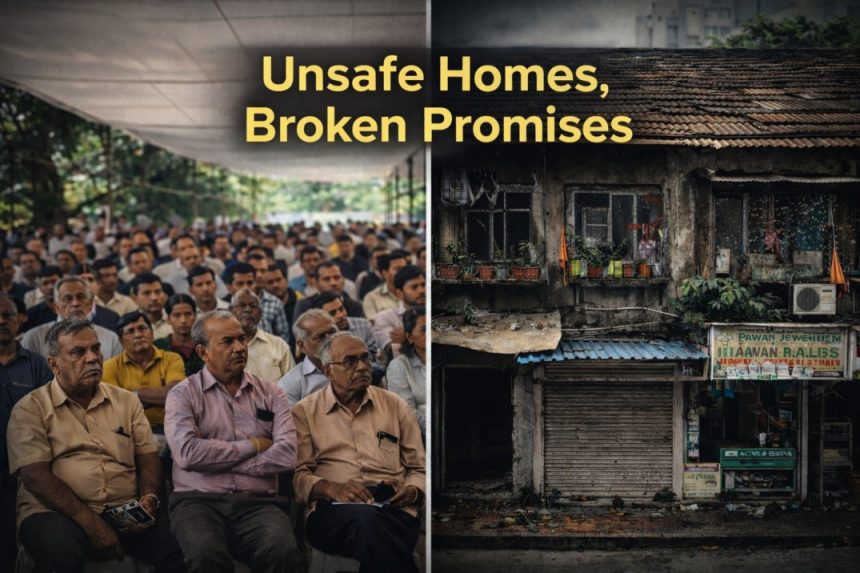

Unsafe Pagdi Chawls and the Right to Life

Mumbai: From a legal and constitutional standpoint, the condition of Pagdi-system chawls constructed prior to 1960 has emerged as a grave public safety and governance crisis. These buildings, many of which are 70 to 100 years old, are structurally weak and classified as dangerous. Forcing residents to continue living in such conditions amounts to a violation of Article 21 of the Constitution of India, which guarantees the Right to Life, Safety, and Human Dignity. Legal experts argue that the State has a constitutional duty to ensure safe and humane housing for its citizens.

Equality Under Law: Alleged Discrimination Against Pagdi Tenants

Advocate Chetan Dinesh Jaiswal, a tenant and legal expert, has stated that denying redevelopment to Pagdi tenants—while similarly dilapidated buildings are redeveloped under SRA, MHADA, and BDD Chawl schemes—constitutes a clear violation of Article 14 (Right to Equality). According to him, issuing an independent and unambiguous Government Resolution (GR) mandating compulsory redevelopment of pre-1960 Pagdi chawls is legally justified, constitutionally mandated, and in the larger public interest.

Staggering Numbers, Escalating Risk

Mumbai has over 13,800 Pagdi chawls, of which more than 10,000 are structurally unsafe, housing nearly 20 to 50 lakh residents. Many families continue to live in these buildings not by choice but due to the absence of any effective redevelopment framework. Decades of stalled policies and prolonged litigation—including pending cases related to Chapter 8A and Section 79A—have converted a housing issue into a serious human safety emergency.

Issue Reaches Maharashtra Legislature

The long-pending demand of Pagdi tenants has now entered formal political discourse. In recent sessions of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council, lawmakers raised concerns over the dangerous condition of old Pagdi buildings and the lack of a clear, time-bound redevelopment policy.

Government Acknowledges the Crisis

During the debate, Deputy Chief Minister Eknath Shinde acknowledged on the floor of the House that thousands of old Pagdi buildings are unsafe. He stated that the government is examining regulatory measures to facilitate redevelopment while balancing the rights of tenants and landlords, signalling official recognition of the gravity of the issue.

Opposition Seeks Stronger Tenant Safeguards

Opposition leaders, including Aaditya Thackeray, cautioned against incomplete or landlord-centric policies. They demanded that any redevelopment framework must provide Pagdi tenants with clear legal status and protection against eviction, coercion, and misuse of bonafide claims, warning that redevelopment without safeguards could lead to displacement rather than justice.

Electoral Pressure Builds

Tenant organisations have highlighted the electoral significance of the issue, noting that over 20 lakh Pagdi chawl residents are registered voters, compared to an estimated 15,000–19,000 landlords. Several groups have adopted the slogan “No Development, No Vote,” warning political parties that continued inaction could result in voter abstention or NOTA as a form of protest.

Prevention Over Compensation

Residents stress that they do not seek compensation after tragedies, but preventive action before lives are lost. As Mumbai aspires to global-city status, activists argue that allowing millions to live in century-old, crumbling structures is morally indefensible and constitutionally unacceptable. With the issue now raised both legally and legislatively, Pagdi chawl tenants insist that compulsory redevelopment is no longer optional—it is a constitutional imperative.